by Kevin Lyons

Winter months are typically fly-tying months for me. From late November through early March, I try to fill my boxes with all the flies I think my wife and I will need for the coming year and maybe create a few new patterns to try out. Having said that, I do occasionally get a spell of what John Gierach called the “Shack Nasties”. I feel the need to be out of my house and out on moving water with a bend in my 5-weight. Mostly this water is the Missouri River, somewhere near Holter Dam.

When should you head to the river?

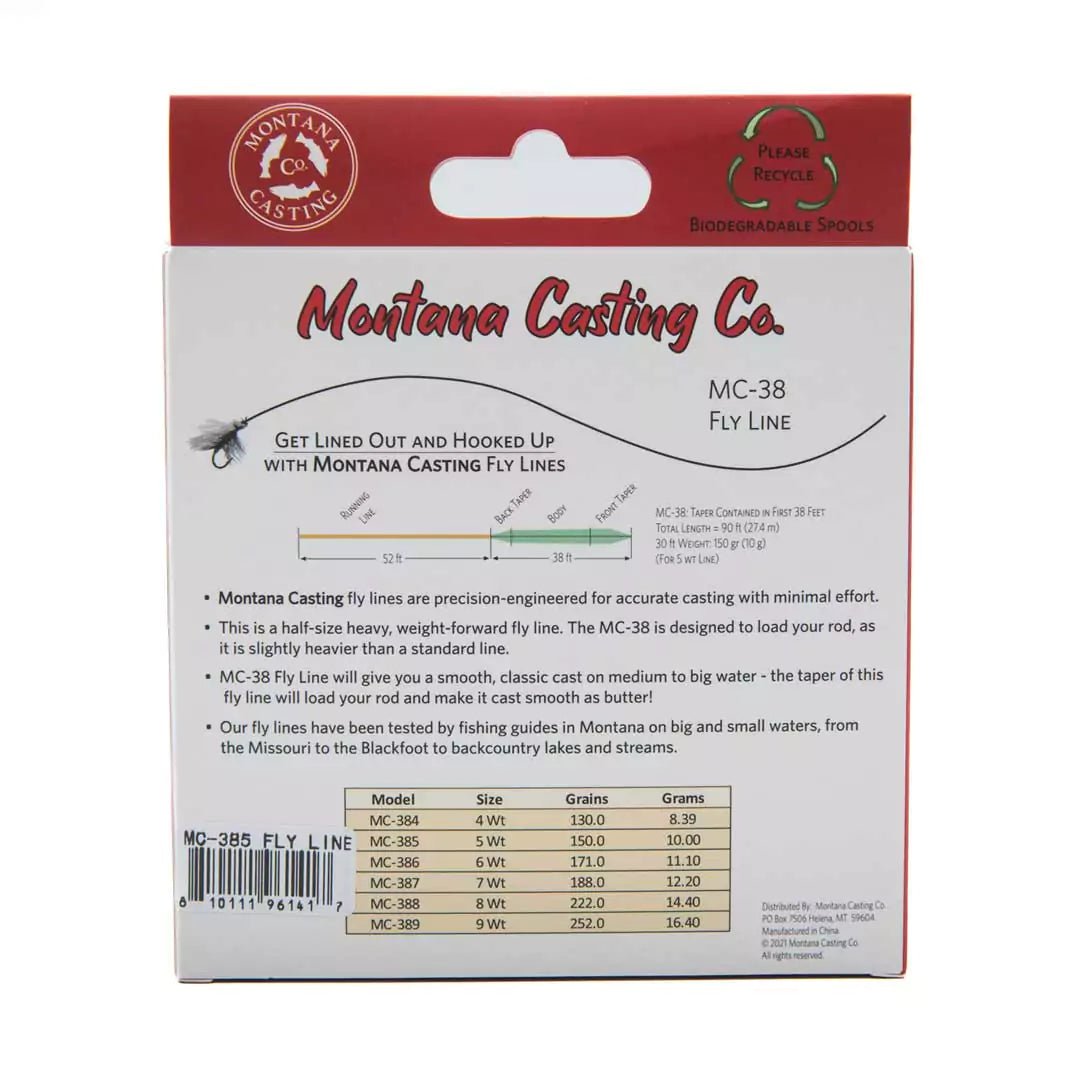

I pick my days carefully. It needs to be at least 28 degrees Fahrenheit, light or no wind, and (hopefully) sunny. Any colder than 28 degrees and my line freezes to my guides so frequently, the aggravation becomes overwhelming. (I’ve tried various anti-icing waxes, and they’re a very temporary solution at best.)

Sunny days are good because the radiant heating from the sun on the rocky bottom can raise the water temperature just enough (maybe only half a degree) to spur insect activity, which in turn encourages the trout to be more cooperative. During these times, the trout will move into normal feeding lies in riffles, flats, and runs. (In winter, I’ve found these lies are almost always adjacent to deep, slow holding-water where the fish spend most of their cold weather hours.) This is not to say cloudy weather is necessarily bad. I’ve had some spectacular days when it was snowing. I just prefer sunny days—possibly for the radiant heating effect the sun has on me.

What gear should you bring?

There are lots of blogs dealing with the safety concerns of fishing in cold water. I don’t have much to add, but I will give one small bit of advice. During cold weather, I wear my clunky, old duck hunting waders. Super insulated boots with 5mm neoprene bodies. While my more fashion-conscious friends are jogging up and down the bank in Simms’ latest trying to get feeling back in their feet, I can stand in 33 degree water for as long as the trout want to eat my flies. I finally convinced my wife to give duck waders a try last year, and life has improved significantly.

What flies should you fish with?

Scuds, sow bugs and midges are the major food sources in winter. Eggs and worms to a lesser extent, if you’re into that sort of thing.

Scuds

The most prevalent types of scud we have on the Mo are Gammarus and Hyalella. Scuds are crustaceans and completely aquatic. They spend their entire life cycles under water with no “hatch” as we see with insects. Scuds range in size from 20 to 5mm, which corresponds to size 10 to 20 hooks. They lay their eggs about five times each year, so, unlike most insects, there is a complete range of sizes available year-round. Unless I have a specific reason not to, I normally fish a size 14.

Scuds are very light sensitive. They spend most of their bright daylight hours either under rocks or in the deepest spots in the river—which is pretty convenient given that deep slow water is where trout spend most of their wintertime hours. Cloudy days can coax scuds from under the rocks and expose them in more traditional feeding lies. The flies I use to imitate winter scuds are the Pink Amex or the Rainbow Czech Nymph. There are plenty of other patterns available—and I’m sure they work great—but those two are the ones I’ve had the most success with. As most Missouri River veterans will tell you, there’s something about pink in winter.

Sow Bugs

Sow bugs are an isopod (another type of crustacean) that looks a lot like a terrestrial pill bug. Our predominate genus on the Missouri is the Caecidotea. Like the scud, they spend their entire life-cycle under water. Sow bugs live about two years. During their first year they molt three to four times to reach maturity. (Interestingly, they only molt half of their shell at a time.) During their second year, they will reproduce three separate times.

They range in size from 15 to 4mm. About a size 12 to 22 hook. Like the scud, I usually fish a size 14. Also like scuds, they are very sensitive to light, making deep, slow runs an ideal place to fish your imitation on bright days. Sow bugs are more tolerant of poor water quality than scuds. I suspect that as our river’s health continues to decline, they will increase in importance. For years, all I used to imitate winter scuds was a Pink Ray Charles with pretty good results. Lately, I’ve had more success with Rainbow Sow Bugs tied with either an orange or purple metallic tungsten bead.

Midges

Midges are available to trout in the Missouri River three-hundred and sixty-five days a year. During winter months and periods between hatches, I suspect they are the major food source. I don’t know how many species there are, but I’m confident there will be trillions of these tiny bugs in any stretch of river you fish. Given their obvious importance, it’s remarkable how little we know about them.

I taught a “Bugs of the Missouri” class for years. I had lots of very experienced anglers, guides, and outfitters take the class and I would always ask them to name a species of mayfly, caddisfly, and stonefly. They invariably could; however, when I asked them to name a species of midge, no one ever did. And no, Zebra Midge is not a species. It’s not really important to know their names, but it is important to know how they live, where they live and when they hatch. The latest Missouri Benthic Macroinvertebrate survey I’ve seen shows 17 distinct species collected at just the Sheep Creek site. I researched each of the listed midges to the best of my ability. I’m sad to say I don’t have much more useful information than when I started; I can tell you the lower mandible length of a Chironominae Pseudochironomus, but nothing about when or where it hatches. That said, I’ve been able to piece together some information about a couple of species that I’ve found to be useful for winter fishing.

The first is Chironominae Microtendipes. Midges are divided up into sprawlers, burrowers, clingers, net builders and tube builders. Micro is a net builder. As I’ve mentioned in past blogs, net building insects need moving water and a constant flow of detritus in the drift. Riffles between Craig and Holter Dam are a perfect environment and are where I’ve found the greatest concentrations of these midges. They emerge throughout the winter, and I believe they are the bugs responsible for the huge mating clusters on the water seen in early spring. The earliest emergence I’ve witnessed was in January. They like sunny days with a water temperature of 34 degrees or warmer. The male adults are 4.5mm (#22) and the females are 8.1mm (#16). Both pupa and adults are olive-dun. (I’ve never collected a larva so I’m not sure if it’s the same color.)

I’ve had success during the hatch fishing a size 22 olive-dun pupa with an orange bead, both in the riffles and the slower runs nearby. I’ve tried a size 16 to imitate the females, but there doesn’t seem to be nearly as many of those, and I don’t do as well. On windless days, the trout will sometimes move into slow, shallow water—normally along the inside bend of the river—and feed on the adults. I pray to the Red Gods for those days so I can get some much-needed dry fly relief. I’ve found that during the first month or so of the hatch, the trout are looking for a single adult midge. I’m not sure the pattern matters much, but I typically fish a size 20 Zelon Midge or Griffith’s Gnat.

Sometime in February the mating clusters on the water become so common that the fish become selective to them. There will be one female and 30 males piled on top of her, all floating down the river and providing a very substantial meal for a wintertime trout. When this happens, I use a size 16 Griffiths Gnat dressed with one of the silicone desiccants. It’s important to keep your fly riding high so that only the hackle points penetrate the water’s surface, imitating the hundreds of tiny feet from one of these insect orgies.

The second winter midge I’ve possibly identified is Chironominae Dicrotendipes. Unlike the net spinning Microtendipes, this midge is a burrower. It lives in slow, silty water where it can dig its hole and feed comfortably. It doesn’t hatch until May, so I don’t use pupa or adult imitations in the winter. I concentrate on the larva. They probably expose themselves frequently during feeding, because the fish definitely look for them. This time of year, they’re about 4.5mm which is a size 20 to 22 hook. They’re also red. (Like most insects that live in a low oxygen environment—down in a burrow in this case—they have to do something to compensate for the lack of oxygen. Most burrowing midges carry an excess of hemoglobin in their bodies to collect and store oxygen when they’re out of their burrows. As anybody who’s taken high school biology can tell you, hemoglobin is red.) I’m sure a size 22 red Zebra Midge would work, but I just wrap some corded red thread around a hook with a few extra turns to create a head and the trout are usually satisfied.

Want to read more field notes from an entomologist?

This article is part of an ongoing series by entomologist Kevin Lyons. He began documenting the bugs he saw while he was out fishing before he even knew their names, a habit that turned into a life-long passion. In 2013, he and his wife moved to Montana and Kevin proceeded to teach fly fishing, entomology, and fly tying at Great Falls College for the next decade. Now retired, he and his wife enjoy a view of the Missouri right outside their backdoor.

If you're interested in seeing more of Kevin's field notes—compiled from years of fly fishing the Mighty Mo—check out the articles below:

What flies should you use on the Missouri River in June?

Flies & Techniques for Fishing the Missouri in July

Fly Fishing Strategies for the Missouri in August

How to Fish the Missouri River in September

Fly Fishing the Missouri in October

Kevin will be back in the spring with more in-depth advice on how to take advantage of the warming weather!

0 comments