Which fly line is right for you?

The answer to that question can depend on a slew of factors, including the species of fish you plan to chase, the flies you plan to fish with, the conditions you’ll be fishing in, the action of your fly rod, and your own personal casting style.

I can already hear my son, Staiger, asking me to get to the point—“Let’s just go fishing already!” So let’s start with the short answer: you can buy just about any fly line for the designated weight of your rod and you’ll be ready to hit the water. If the short answer was all you wanted, then you can stop reading here. Have fun out there!

The long answer gets a bit more technical, and it involves a general understanding of a few different factors:

- The relationship between line weight and rod deflection

- How factors such as target species, fly casting ability, and fly rod action affect your ability to build energy behind a fly

- The ways in which different tapers can influence your cast

For those of you interested in understanding the differences between fly lines and why you might choose one over the other, this is the first in a three-part series that will dive into the nitty-gritty of all things fly line. In today’s post, we’ll touch on the first two bullet points in our list above.

What’s the connection between fly line weight and fly rod weight?

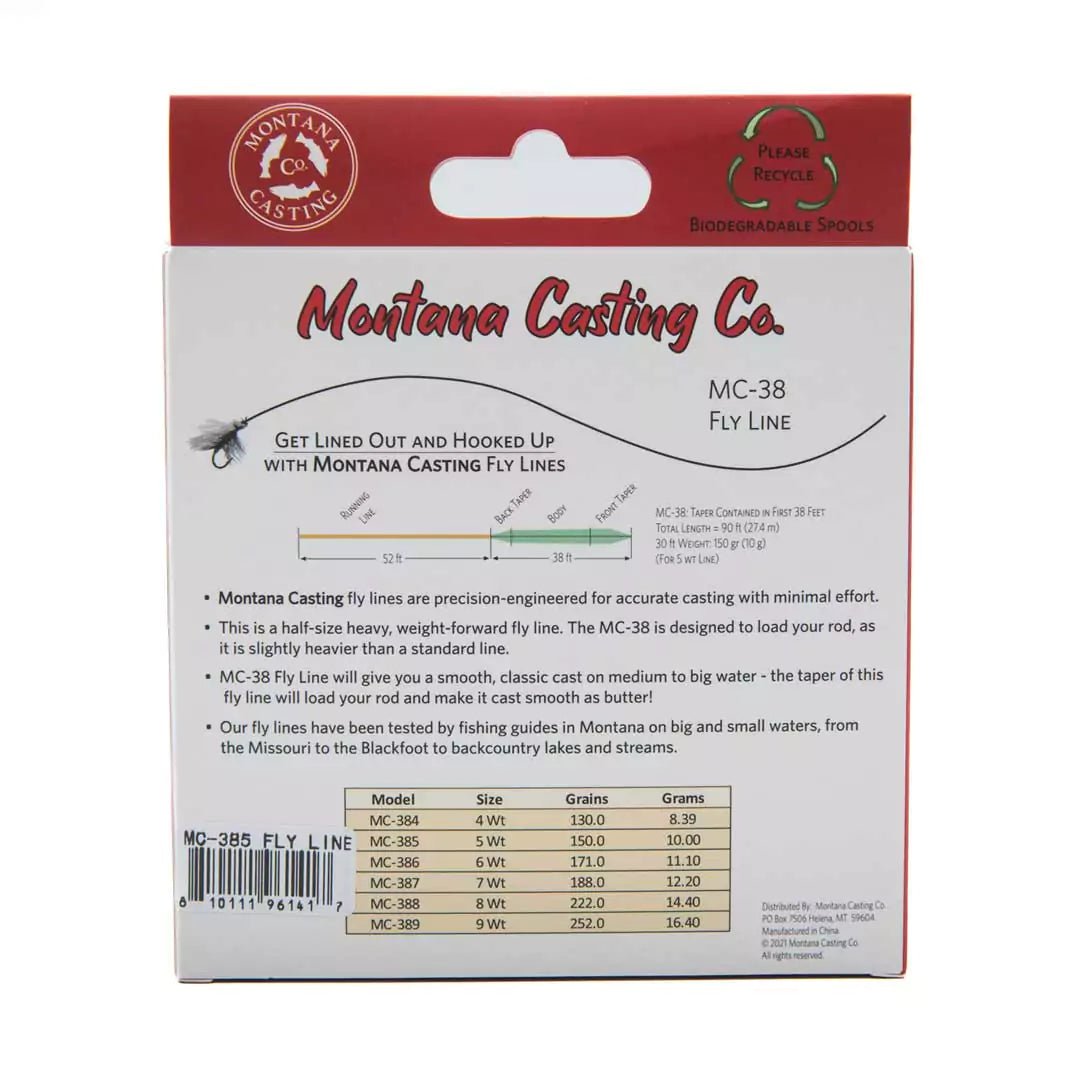

It’s easy to get deep into the weeds while discussing line weight, but we’ll start with some basics. The American Fly Fishing Trade Association (AFFTA) specifies a fly line’s weight based on the first 30 ft of a fly line minus the level line. (Level line refers to the section of line leading up to the beginning of the taper of the head of the fly line—more on that in the section on taper!)

The mass of the first 30 ft of line is measured in grains or grams. One grain is equal to 1/7000th of a Ib. One gram is equal to approximately 15.5 grains.

At its simplest, line weight refers to a number between 1 and 15 that corresponds with the range of line masses that will optimally load a rod of the same number.

To determine what fly line weight will allow for optimal loading of a rod under average conditions, we use a system called the Common Cents System (CCS).

What is the Common Cents System and how is it used?

The CCS makes the broad assumption that a rod is loaded when, fixed by its grip on a horizontal support, its tip has flexed vertically downward one third of the total length of the rod (not including the reel seat and cork). Therefore, if you know how many inches you need your rod tip to deflect vertically from the horizontal position, you can determine how much weight it will take to achieve a loaded state. The CCS does this with standard U.S. pennies and, through a series of conversions, allows you to determine the proper line weight for any given fly rod.

Let’s walk through an example. If you have a 9-foot fly rod that is 108 inches in total length, you’ll want to start by subtracting the length of the reel seat and cork—generally around 11 inches. This gives you a rod length of 97 inches. Now divide that by three and you’ll get 32.3 inches. 32 inches is the amount of deflection (flex) the rod needs to have from a level position in order to be loaded.

Next, you’ll hang a plastic bag with a paperclip to the end of the fly rod and see how many pennies it takes to give the rod that 32 inches of deflection. In this example, let’s say it takes 43 pennies. You’ll need the conversion table below to convert the number of pennies into its corresponding rod/fly line weight. If it takes 43 pennies to deflect the rod 32 inches, then the rod will (in theory) load most efficiently with a 5 weight fly line.

The CCS conversion table also allows you to convert the number of pennies into a number of other metrics that pertain to your fly rod’s performance, such as the Effective Rod Number (ERN)—a measure of your fly rod’s general power or backbone. Continuing with our example, 43 common cents (or pennies) correspond with an ERN of approximately 5.5—meaning it’s a mid-range 5weight fly rod. (All rods with ERN values ranging from 5.0 to 5.99 can be considered 5 weight rods; of course, the higher the ERN number, the closer you get to being a 6 weight fly rod. Conversely, the lower the ERN number, the closer your rod gets to being a 4 weight).

You’ll also see Defined Bending Index (DBI), which is a combination of the rod’s ERN and Action Angle (AA). Generally speaking, the higher the ERN, the greater the power. The higher the AA, the faster the action. Thus, DBI is a metric that allows for a swift comparison of the relative power and action of any fly rod.

Why do we care about line weight (or, more accurately, mass)?

While the Common Cents System gives us a good basis for determining what fly line weight works for a given rod under average conditions, you won’t necessarily be contending with average conditions on the water. The weight of your fly, the weather, the distance you need to cast, and your skill level can all influence which line will help you achieve optimal loading.

Let’s think about energy for a moment. A good cast is all about building potential energy and converting it into the right amount of kinetic energy to launch your fly across the water and land the perfect presentation. If you want to get into the physics of it, kinetic energy (or the energy of motion) is determined by the following equation:

Kinetic Energy = (½)mv^2

This means there are two important factors to consider in your cast: how much mass (m) you’ve got in your fly line and how much velocity (v) you can give that mass. The more you have of either one of these, the more kinetic energy you’ll have driving your fly forward.

We can apply this concept by first thinking about the mass of your chosen fly. Since the fly line is what ultimately propels your fly forward, a larger fly will need a heavier fly line to generate the energy needed to cast it effectively. The same thought process goes for windy conditions: if you’re fighting the wind, you will need to generate more energy to overcome the wind. Therefore, a heavier line will likely be ideal for windier conditions.

That said, if you’re a skilled caster or have a faster action rod and can generate a lot of line speed, you may not need as heavy of a line to generate the same amount of kinetic energy as someone who is less experienced or working with a softer action fly rod.

Practically speaking, this might look like choosing a line that is one weight class above or below the AFFTA recommended weight, depending on your needs. If you’re just getting into fly fishing, however, it’s probably best to stick with the line weight corresponding with your rod weight—after some time on the water, you’ll start to feel where you might need a heavier or light line weight.

In our next post about fly lines, we’ll dive into taper—what is it and how does it impact your cast?

Disclaimer: Yes, we have mercilessly dissected and weighed many fly lines over the years to get our fly rods and fly lines to be exactly what we want them to be. I know it's terrible, but it was done in the name of science!

Have questions? Want to talk shop? We’re always happy to chat. Leave a comment below, send us an email at gethookedup@montanacastingco.com or give us a call at 406-285-1452. Happy fishing!

1 comment

Impressive great work n I like the science C